Emmanuelle Courrèges on the African Designers Breaking New Ground.

African fashion has never received as much attention as it has in recent years. Previously absent from international fashion circles, it blazed its way into the official fashion week schedules in Paris, Milan, and New York. Majestic kente cloth by Cameroonian Imane Ayissi; aso-oke fabric woven in effusive rainbow colors by Nigerian Kenneth Ize; boldly poetic and politicized womenswear by South African Thebe Magugu, winner of the 2019 LVMH Prize for Young Fashion Designers; and the joyful intermingling of batik and indigo by Ghanaian Studio One Eighty Nine were all avidly received.

This new wave sweeping the world today is born not only out of an ebullient creativity in Africa, but also out of a powerful force, a singular voice that is rising up and opening a new chapter in fashion, as was the case with the Japanese designers and the Antwerp Six1 in the 1980s. In her coverage of Imane Ayissi’s first Paris Haute Couture show, French journalist Sophie Fontanel writes, “It refreshes the eye and exalts the spirit.”

Although Africa has long inspired Western fashion, African designers are now weaving a new aesthetic that reflects a continent-wide demand—for cultural reappropriation and the invention of a language exclusive to Africa. From Cape Town to Abidjan, and from Marrakech to Kigali, designers, photographers, visual artists, and bloggers are shaping what Senegalese sociologist Alioune Sall, in his prescient book Africa 2025: What Possible Futures for Sub-Saharan Africa?, calls “a cultural renaissance.”

In the most optimistic of the four scenarios presented in 2003 by the founder and executive director of the African Futures Institute, Sall writes that this renaissance “allows African societies to look back at their past in a positive light. It allows Africans to mark their territory. It allows them to invent themselves in the world of the twenty-first century.” This renaissance champions African cultures, emancipation of the African people, Pan-Africanism, and freedom of expression.

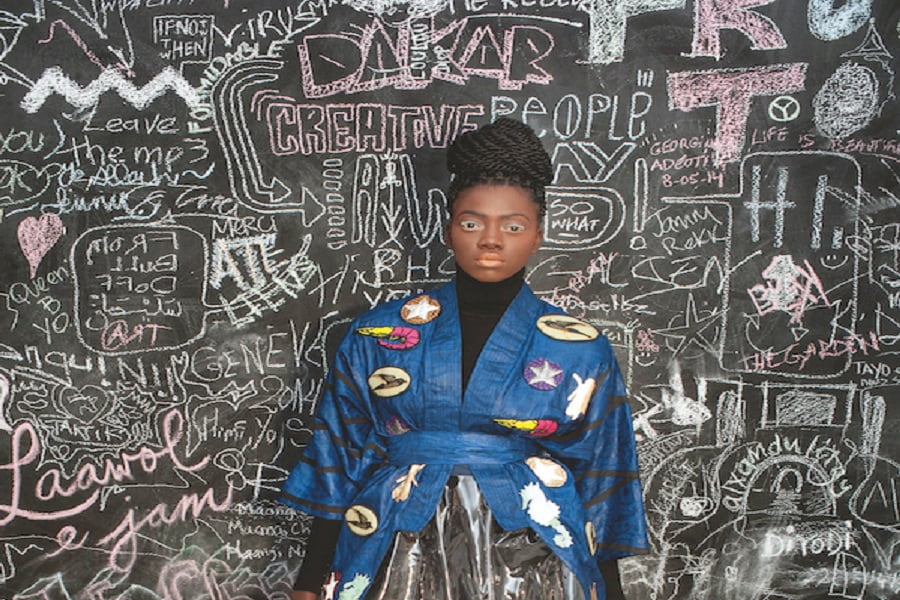

Selly Raby Kane. © Jean-Baptiste Joire.

In the mid-1960s, twenty years after World War II, London, riding a wave of economic growth, became the stage for a new lifestyle expressed against a backdrop of demonstrations and sexual liberation. Protesting against the atomic bomb and the Vietnam War—struggles that were evoked in the pop music that flowed from pirate radio stations—the city’s youth, middle and working classes alike, shattered establishment codes in their glorification of the right to indulge in pleasure, to exist, and to reinvent the world. Young men started wearing low-rise pants, prints, and psychedelic colors, while women adopted Mary Quant’s miniskirt and cropped hairstyles created by Vidal Sassoon.

Fashion photographer David Bailey immortalized the model Twiggy; and the clubs on the King’s Road thrummed to the beat of the Beatles, the Who, Pink Floyd, and the Rolling Stones. Time dedicated its April 15, 1966 issue to the creative ferment sweeping the city. The magazine’s cover and an in-depth article cemented the city’s reputation with the headline “London: The Swinging City.” But Swinging London represented more than just a “lust for life” and baby-boomers’ access to consumer goods; it epitomized a cleft in history, a genuine cultural revolution.

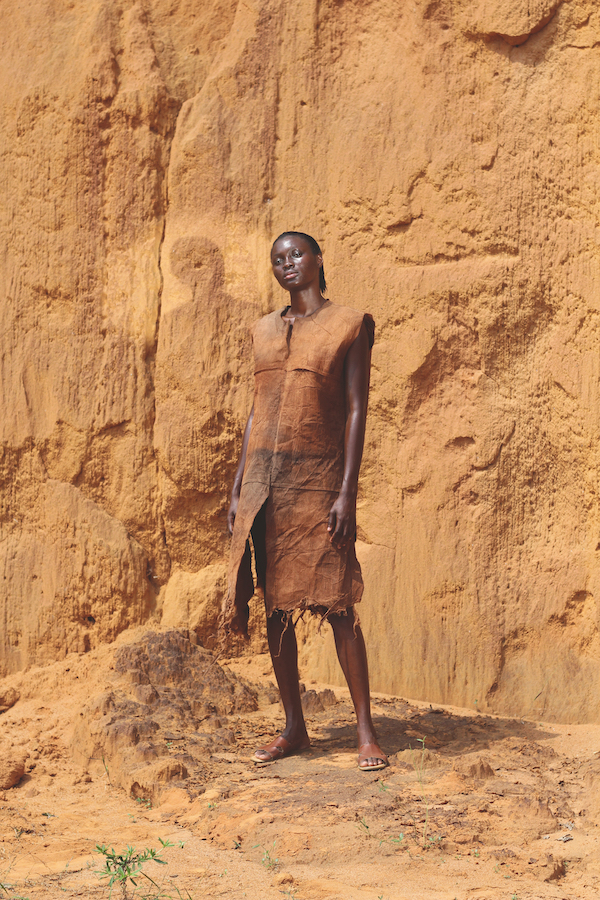

I.AM.ISIGO (brand created by Bubu Ogisi), dress in tapa cloth from the “Supreme Higher Entity” collection, spring–summer 2020, modeled by Tatiana Sinon. Art direction, hair, and makeup: Bubu Ogisi. © Kader Diaby.

It may seem inconceivable to compare a city to a continent, especially considering that Africa is all too often perceived as a single country, and that the West still tends to view Africa through a Eurocentric lens. A shared spirit nevertheless unites the events on London’s Carnaby Street in the 1960s with recent developments on the African continent. Fashion designers and photographers, textile designers, makeup artists, and cultural agitators all contribute to shaping this new “Swinging Africa” whose vibrant energy is making waves around the world.

Using language to connect these two tectonic historical shifts does not create an artificial relationship, nor amount to a comparison in the strict sense of the term; rather it positions Africa, in London’s wake, within the history of fashion, as well as within the history of ideas. For, after all, fashion is not merely sartorial in nature, and the current creative period contributes to what Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe calls “the reversal of the African sign.” Fashion may be an industry and a system, but it is first and foremost a means of expression for societies, eras, and people.

Erykah Ijeoma Achebe, self-portrait, 2020. Hair: Wow African Hair Braiding. © Erykah Ijeoma Achebe.

In the last fifteen years, African societies have undergone a number of political, economic, demographic, and socio-cultural changes. A middle class has developed in many countries, including Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana, and Ivory Coast. Its members, along with the elite, dictate taste and purchase the products that African cultural entrepreneurs produce. Lifestyles are changing. Without eclipsing traditional tailors, who still hold sway in many circumstances, concept stores and e-commerce sites are multiplying, and they celebrate a new form of fashion design inspired by the continent’s diverse cultural heritage. Although many of those with purchasing power continue to favor international brands, this is gradually changing. There was a time, Sall reminds us, “when children who dared to speak the local language in school were forced to wear a dunce cap”—a way of emphasizing that taste has long been shaped by edicts delivered from outside Africa—but now Instagram is flooded with pages urging people to #buyafrican or #wearanafricandesigner.

Selly Raby Kane, look from the “Dakar City of Birds” collection, fall–winter 2015. © Jean- Baptiste Joire.

Fashion weeks in Dakar, Lagos, and Johannesburg6 have played an important role in the emergence of ready-to-wear. Taking place every year for the past few decades, they have enabled the best designers in Africa to produce together, publicizing their work in Africa and in the world, and securing support from influential individuals. Founded by designers Adama Paris (Senegal), Omoyemi Akerele (Nigeria), and Lucilla Booyzen (South Africa), these events have contributed to generating a new enthusiasm for contemporary African fashion. Some brands have managed to achieve a level of desirability on a par with international labels by being featured in locally produced television series or in Nollywood films, or worn by personalities like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (who can often be seen wearing Maki Oh, Nkwo, or Gozel Green), Solange Knowles, and Michelle Obama.