Pollution and greenhouse gas emissions have fallen across continents as countries try to contain the spread of the new coronavirus. Is this just a fleeting change, or could it lead to longer-lasting falls in emissions?

In a matter of months, the world has been transformed. Thousands of people have already died, and hundreds of thousands more have fallen ill, from a coronavirus that was previously unknown before appearing in the city of Wuhan in December 2019. For millions of others who have not caught the disease, their entire way of life has changed by it.

The streets of Wuhan, China, are deserted after authorities implemented a strict lockdown. In Italy, the most extensive travel restrictions are in place since World War Two. In London, the normally bustling pubs, bars and theatres have been closed and people have been told to stay in their homes. Worldwide, flights are being cancelled or turning around in mid-air, as the aviation industry buckles. Those who are able to do so are holed up at home, practicing social distancing and working remotely.

It is all aimed at controlling the spread of Covid-19, and hopefully reducing the death toll. But all this change has also led to some unexpected consequences. As industries, transport networks and businesses have closed down, it has brought a sudden drop in carbon emissions. Compared with this time last year, levels of pollution in New York have reduced by nearly 50% because of measures to contain the virus.

In China, emissions fell 25% at the start of the year as people were instructed to stay at home, factories shuttered and coal use fell by 40% at China’s six largest power plants since the last quarter of 2019. The proportion of days with “good quality air” was up 11.4% compared with the same time last year in 337 cities across China, according to its Ministry of Ecology and Environment. In Europe, satellite images show nitrogen dioxide (NO2) emissions fading away over northern Italy. A similar story is playing out in Spain and the UK.

Only an immediate and existential threat like Covid-19 could have led to such a profound change so fast; at the time of writing, global deaths from the virus had passed 20,000, with more than 400,000 cases confirmed worldwide. As well as the toll of early deaths, the pandemic has brought widespread job losses and threatened the livelihoods of millions as businesses struggle to cope with the restrictions being put in place to control the virus. Economic activity has stalled and stock markets have tumbled alongside the falling carbon emissions. It’s the precisely opposite of the drive towards a decarbonised, sustainable economy that many have been advocating for decades.

A global pandemic that is claiming people’s lives certainly shouldn’t be seen as a way of bringing about environmental change either. For one thing, it’s far from certain how lasting this dip in emissions will be. When the pandemic eventually subsides, will carbon and pollutant emissions “bounce back” so much that it will be as if this clear-skied interlude never happened? Or could the changes we see today have a more persistent effect?

The first thing to consider, says Kimberly Nicholas, a sustainability science researcher at Lund University in Sweden, is the different reasons that emissions have dropped. Take transport, for example, which makes up 23% of global carbon emissions. These emissions have fallen in the short term in countries where public health measures, such as keeping people in their homes, have cut unnecessary travel. Driving and aviation are key contributors to emissions from transport, contributing 72% and 11% of the transport sector’s greenhouse gas emissions respectively.

We know that for the duration of reduced travel during the pandemic, these emissions will stay lowered. But what will happen when measures are eventually lifted?

In terms of routine trips like commuting, those miles left untravelled during the pandemic aren’t going to come back – you’re not going to travel to the office twice a day to make up for all the times you worked from home, says Nicholas. But what about other kinds of travel – might the cabin-fever of self-isolation encourage people to travel more when the option is there again?

“I can see arguments in both directions,” says Nicholas. “It may be the case that people who are avoiding travel right now are really appreciating spending time with families and focusing on those really core priorities. These moments of crisis can highlight how important those priorities are and help people focus on the health and wellbeing of family, friends and community.”

If this change in focus as a result of the pandemic sticks, then this could help to keep emissions lower, Nicholas suggests.

But there’s another way it could go. “It could also be that people are putting off long-distance trips but plan on taking them later,” Nicholas says. Frequent flying forms a large part of the carbon footprint for people who do it regularly, so these emissions could simply come back if people return to their old habits. (Read more about how to go on a “flight diet”.)

Historic epidemics

This is not the first time an epidemic has left its mark on atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. Throughout history, the spread of disease has been linked to lower emissions – even well before the industrial age.

Julia Pongratz, professor for physical geography and land use systems at the Department of Geography at the University of Munich, Germany, found that epidemics such as the Black Death in Europe in the 14th Century, and the epidemics of diseases such as smallpox brought to South America with the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in the 16th Century, both left subtle marks on atmospheric CO2 levels, as Pongratz found by measuring tiny bubbles trapped in ancient ice cores.

Those changes were the result of the high death rates from disease and, in the case of the conquest of the Americas, from genocide. Other studies have found that these deaths meant that large tracts of previously cultivated land was abandoned, growing wild and sinking large quantities of CO2.

The impact from today’s outbreak is not predicted to lead to anywhere near the same number of deaths, and it is unlikely to lead to widespread change in land use. Its environmental impacts are more akin to those of recent world events, such as the financial crash of 2008 and 2009. “Then, global emissions dropped immensely for a year,” says Pongratz.

The reduction in emissions then was largely due to reduced industrial activity, which contributes carbon emissions on a comparable scale to transport. Combined emissions from industrial processes, manufacturing and construction make up 18.4% of global anthropogenic emissions. The financial crash of 2008-09 led to an overall dip in emissions of 1.3%. But this quickly rebounded by 2010 as the economy recovered, leading to an all-time high.

“There are hints that coronavirus will act the same way,” says Pongratz. “For example, the demand for oil products, steel and other metals has fallen more than other outputs. But there are record-high stockpiles, so production will quickly pick up.”

One factor that could influence whether or not these emissions bounce back is how long the coronavirus pandemic lasts. “At the moment that’s hard to predict,” says Pongratz. “But it could be that we see longer-term and more substantial effects. If the coronavirus outbreak continues to the end of the year then consumer demand could remain low because of lost wages. Output and fossil fuel use might not recover that quickly, even though the capacity to do so is there.”

Overall 2020 may still see a drop in global emissions of 0.3% – less pronounced than the crash of 2008-09

The OECD predicts that the global economy will still grow in 2020, albeit growth predictions have fallen by half because of coronavirus. But even with this recovery, researchers such as Glen Peters of the Center for International Climate and Environment Research in Oslo have noted that overall 2020 may still see a drop in global emissions of 0.3% – less pronounced than the crash of 2008-09, but also with an opportunity for less rebound if efforts to stimulate the economy are focused towards sectors such as clean energy.

Force of habit

There are other, less direct ways that coronavirus could have a longer-term impact on sustainability, too. One is pushing the climate crisis off people’s minds, as the more pressing concern of immediately saving lives takes precedence.

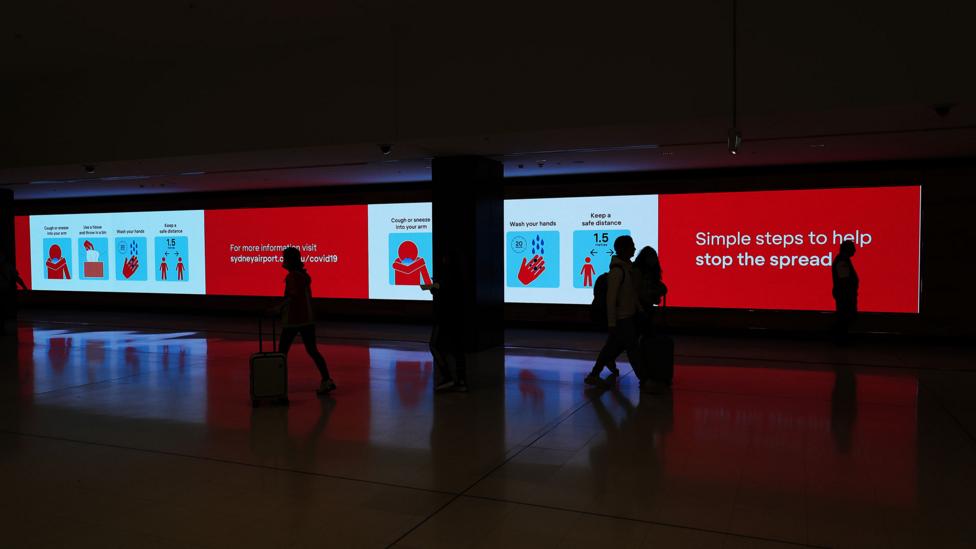

Warnings greet travellers at Sydney International Airport. From Wednesday 25 March, all international travel to Australia was banned (Credit: Getty Images)

The other is quite simply making discussion around climate more difficult as mass events are postponed. Greta Thunberg has urged for digital activism to take the place of physical protests due to the coronavirus outbreak, while the biggest climate event of the year, COP26, is currently still scheduled to be held in November. COP26 is expected to draw 30,000 delegates from around the world. The conference organisers are still working towards hosting the event in Glasgow, a COP26 spokesperson says, although they are in frequent contact with the UN and the current COP president in Chile, among other partners.

There may be another way that the behavioural changes taking place around the world could carry over beyond the current coronavirus pandemic.

“We know from social science research that interventions are more effective if they take place during moments of change,” says Nicholas.

A 2018 study led by Corinne Moser at Zurich University of Applied Sciences in Switzerland found that when people were unable to drive and given free e-bike access instead, they drove much less when they eventually got their car back. While a study in 2001 led by Satoshi Fujii at Kyoto University in Japan found that when a motorway closed, forcing drivers to use public transit, the same thing happened – when the road reopened, people who had formerly been committed drivers travelled by public transport more frequently.

Motorways have emptied in Auckland as the New Zealand government increases travel restrictions (Credit: Getty Images)

So times of change can lead to the introduction of lasting habits. During the coronavirus outbreak, those habits that are coincidentally good for the climate might be travelling less or, perhaps, cutting down on food waste as we experience shortages due to stockpiling.

Community action

One response to the coronavirus outbreak that has drawn mixed reactions from climate scientists is the ways that many communities have taken big steps to protect each other from the health crisis. The speed and extent of the response has given some hope that rapid action could also be taken on climate change if the threat it poses was treated as urgently.

“It… shows that at the national, or international level, if we need to take action we can,” Donna Green, associate professor at University of New South Wales’s Climate Change Research Centre in New Zealand, told CNN. “So why haven’t we for climate? And not with words, with real actions.”

But for others, such as Nicholas, the community action has sparked hope for the climate in the longer term. And Pongratz sees the time afforded by self-isolation as a good opportunity for people to take stock of their consumption.

It’s safe to say that no one would have wanted for emissions to be lowered this way. Covid-19 has taken a grim global toll on lives, health services, jobs and mental health. But, if anything, it has also shown the difference that communities can make when they look out for each other – and that’s one lesson that could be invaluable in dealing with climate change.