In Tibetan Buddhism, the group of tantric techniques known as milam aim to reveal the illusory nature of waking life by having practitioners perform yoga in their dreams. It’s a ritualised version of one of the most mysterious faculties of the human mind: to know that we’re dreaming even while asleep, a state known as lucid dreaming.

Lucidity (awareness of the dream) is different to control (having power over the parameters of the experience, which can include summoning up objects and people, attaining superpowers and travelling to fantastic worlds). But the two are closely linked, and many ancient spiritual traditions teach that dreams can yield to us with time and practice. How?

As a researcher in psychology, I’ve approached this question scientifically. Despite the long history of lucid dreaming in human societies, it wasn’t until 1975 that researchers came up with an ingenious way to verify the phenomenon empirically. The first step was the insight that the muscles of the eyes are not paralysed during sleep, unlike the rest of the body. Inspired by the work of Celia Green, the British hypnotherapist Keith Hearne reasoned that this should allow lucid dreamers to communicate with the outside world.

He had an experienced dreamer spend several nights in a sleep lab, and instructed him to flick his eyes left to right with pre-arranged signs when he finally entered a lucid dream. The volunteer succeeded, and Hearne was able to record the movements – which corresponded with the Rapid Eye Movement (REM) phase of sleep. Many later studies have since replicated these findings.

Yet distilling reliable methods for inducing lucid dreams has proved to be a struggle. Although around 40 studies have been conducted on the subject since the 1970s, most of them reported scant success – in most studies, between around 3 per cent and 13 per cent of attempts resulted in a lucid dream.

when I first started my PhD, I noticed that most of the research was limited by such things as the small sample sizes and unreliable measurements – so I set about trying to address the limitations and investigate some of the more promising methods.

In the study I published with colleagues at the University of Adelaide, the best technique turned out to be something called Mnemonic Induction of Lucid Dreams (MILD), originally developed in the 1970s by the American psychophysiologist Stephen LaBerge. It involves the following steps:

1. Set an alarm for five hours after you go to bed.

2. When the alarm sounds, try to remember a dream from just before you woke up. If you can’t, just recall any dream you had recently.

3. Lie in a comfortable position with the lights off and repeat the phrase: ‘Next time I’m dreaming, I will remember I’m dreaming.’ Do this silently in your mind. You need to put real meaning into the words and focus on your intention to remember.

4. Every time you repeat the phrase at step 3, imagine yourself back in the dream you recalled at step 2, and visualise yourself remembering that you are dreaming.

5. Repeat steps 3 and 4 until you either fall asleep or are sure that your intention to remember is set. This should be the last thing in your mind before falling asleep. If you find yourself repeatedly coming back to your intention to remember that you’re dreaming, that’s a good sign it’s firm in your mind.

We relied on data from 169 people from all over Australia, who kept a dream journal so we could measure the effect of induction techniques against their ‘baseline’ tendency. More than half the people who used MILD ended up having at least one lucid dream in the week they started practising; they also went from experiencing these dreams about one night out of 11 to about one night in six. These findings are very exciting, and are some of the highest success rates reported in the scientific literature.

Surprisingly, the number of times that people repeated the mantra about remembering that they’re dreaming, or even the amount of time spent on MILD overall, did not predict success. Instead, the most important factor was being able to complete the technique and then go back to sleep quickly. In fact, it proved almost twice as effective when people fell asleep within five minutes after setting their intention. If you want to try this for yourself, you’ll need to experiment in order to get the right level of wakefulness when the alarm goes off – enough to allow you to complete the steps, but not so much that you’ll struggle to doze off again. Doing the technique after five or so hours of sleep is important, too: most of our dreams occur in the last two to three hours before waking, and you want to minimise the time between finishing the technique and entering REM sleep.

It takes a bit of practice, but if you’re lucky you might even have a lucid dream using MILD on your first night. If you do become aware that you’re dreaming, it’s important to stay calm, since intense emotions can trigger a premature awakening. And if the dream starts to fade or seems unstable, you can try rubbing your hands together vigorously from within the dream. It sounds strange, but this strategy works by flooding the brain with sensations from within the dream, which decreases the chance of becoming aware of your sleeping physical body, and waking up.

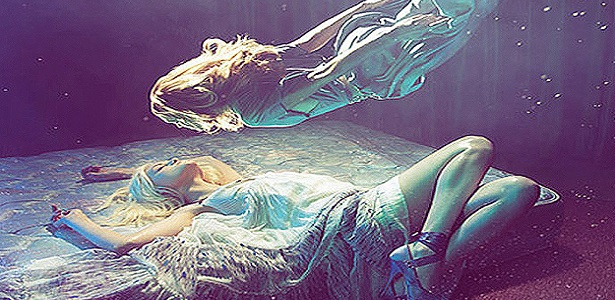

Aside from the sheer joy of being able to bend an imaginary world to your will, there’s a range of additional psychological benefits to lucid dreaming. For one, it can help with nightmares: simply knowing that you’re dreaming often brings relief during a nasty episode. You might also be able to use dreams to process trauma: confronting what’s haunting you, making peace with an attacker, escaping the situation by flying away, or even just waking up. Other potential applications include practising sporting skills by night, having more ‘active’ participants for studies about sleep and dreaming, and the pursuit of creative inspiration. With practice, our dream state can feel almost as vivid to us as the world itself – and leaves you wondering, perhaps, where fantasy ends and reality begins.![]()

By Denholm Aspy. This article was originally published at Aeon and has been republished under Creative Commons.